What

CEOs must do to Succeed

To succeed, CEOs must:

- Take action; don’t hesitate or hedge your bets.

- Cultivate trusted advisors and accept their feedback.

- Seek clarity and alignment with the board on strategic issues.

In the face of this transformation, certain leadership experiences transcend time and circumstance. Regardless of company size, industry, country or culture; CEOs confront four undeniable realities: a high degree of risk, intense loneliness, lack of feedback and difficulty letting go. These certainties are unique to the CEO role.

The following insights can help leaders reflect on their roles as CEOs and realize that they are not alone in what they experience. These realities have been endured by essentially every CEO who served before them, are encountered by each of their peers today and, without question, will be experienced by their successors tomorrow.

The following insights can help leaders reflect on their roles as CEOs and realize that they are not alone in what they experience. These realities have been endured by essentially every CEO who served before them, are encountered by each of their peers today and, without question, will be experienced by their successors tomorrow.

“You have to take action; you can’t hesitate or hedge your bets. Anything less will condemn your efforts to failure.”—Andy Grove, Intel

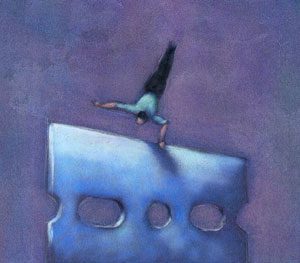

A High-Wire Act

Virtually all CEOs with whom I have worked compare their leadership experience to that of a high-wire act. Much like aerialists, CEOs are engaged in a risky profession that requires a great deal of steadiness, care and composure.

High above the ground, they struggle to maintain their balance. All the while, an attentive audience watches; many hope for success—while some await the slightest misstep.

Conditions that can cause CEOs to lose their footing include lack of confidence, shortened tenures and failure to align with the board.

At these heights, self-confidence is mandatory for survival. As Andrew Grove, the former CEO of Intel, said, “You have to pretend you’re 100 percent sure. You have to take action; you can’t hesitate or hedge your bets. Anything less will condemn your efforts to failure.

Even with self-assurance, the balancing act can be perilous if rushed. A study by Booz & Co. reported that the tenure of CEOs during the past decade has decreased from an average of eight years to six, leaving far less time within which to accomplish considerably more. This pressure can cause rash action in the pursuit of success.

Recent headlines show that the lack of board alignment increases the chance of a fatal misstep. In the first quarter of 2011, the CEOs of Acer, Advanced Micro Devices (AMD) and Vodafone—just to name a few—left their posts, reportedly due, in part, to disagreements with their boards.

To an outsider, CEO Dirk Meyer had been an asset for AMD: In less than two years, he spun off the firm’s manufacturing arm, returned AMD to profitability and launched three different computer processor series. However, the board wanted more focus on newer mobile devices. Concerned he wasn’t doing enough in that area, the board eventually forced his departure.

Without question, today’s leaders walk a razor’s edge. This CEO reality is one of high risk and high visibility—balancing time, resources and results across a chasm of complexity, uncertainty and skepticism.

Lonely Doesn’t Begin to Describe It

William Mitchell, former CEO of Arrow Electronics, once said, “You can watch CEOs. You can be next to CEOs. You can report to CEOs. You can study CEOs. But, until you actually sit in that chair, you do not know what it’s like.”

Each CEO I know who stepped into the position was hit with the realization of how much bigger, lonelier and more complex it was—compared to anything else they have done. All CEOs soon realize they have much less control than they originally thought. Many experience a sense of insecurity and detachment not readily apparent, for they have learned to conceal those feelings so well.

John Hanson, former chairman, president and CEO of mining company Joy Global (formerly Harnischfeger Corporation), is widely considered to be extraordinarily strong and resilient, yet he has reflected on the isolation he felt during a particularly rough time shortly after joining Harnischfeger as president. He was forced to take Harnischfeger through Chapter 11 bankruptcy and he described the experience as one of the toughest, emotional times in his 30 plus-year career. However, thanks to John’s focus on what was best for the organization and his ability to make hard decisions, the company remained intact.

What intensifies these feelings of aloneness is the fact that there are few people in whom the CEO can genuinely confide. Who else has the contextual perspective, vision and responsibility equal to that of the CEO at a particular moment in time?

What intensifies these feelings of aloneness is the fact that there are few people in whom the CEO can genuinely confide. Who else has the contextual perspective, vision and responsibility equal to that of the CEO at a particular moment in time?

Feedback is Hard to Find—and to Accept

Solid feedback is rarely available to the top leader and even more difficult to accept. It has been widely reported that former Merrill Lynch CEO Stanley O’Neal ignored critical feedback, confirming that he didn’t tolerate dissenting opinions. Rajat Gupta, the former managing director of McKinsey & Company, now under investigation for insider trading, also struggled to accept feedback. Friends warned him about the questionable background of Galleon Group’s Raj Rajaratnam, but he waved them off.

Whether from internal or external sources, CEOs find it challenging to accept information and advice at face value, let alone trust what they hear. They are in constant fear that they may be exposing themselves to agenda-rich, instead of insight-rich, information.

Complicating matters further is the concern that CEOs can fear appearing weak for even seeking feedback. Thus, many don’t ask for it at all.

“When you are a CEO you’ve got to realize in the end that you have to share the burden.”—Roger Deromedi, formerly of Kraft Foods

The challenge is two-pronged: CEOs must first find people to whom they can truly trust to open up and, then, they need to make themselves psychologically open to the feedback offered. As Roger Deromedi, the former CEO of Kraft Foods, told me, “When you are a CEO, you’ve got to realize in the end that you have to share the burden. And if you try to carry the entire burden yourself, it can take a significant toll.”

Letting Go May be Harder Than You Think

On the eve of her departure from Xerox, then-CEO Anne Mulcahy expressed surprise at how hard it was to relinquish the post. In an interview with Bloomberg BusinessWeek, Anne reflected, “You get here and it’s very hard to let it go. So there is a part of me that is struggling…”

Many CEOs go into the role believing that they will be different—that they will have little problem stepping down. However, when the horizon comes into view at the mid-point of their tenure, their attitudes suddenly shift—especially if their vision is not yet fully realized.

The status that comes with the position of CEO also brings power and, human nature being what it is, power is the most difficult force to surrender.

Such was the case with the CEO of a Fortune 500 company. An ambitious executive who very much wanted the top job, he finally achieved his goal and proved to be an effective, much-adored leader. However, when it came to discussing plans for stepping down, his ambivalence towards his successor surfaced strongly. Consequently, the board worried these mixed messages were getting in the way of making a final decision. Like many CEOs, his intellect understood the need to move on, but his emotional readiness lagged behind. With guidance from a variety of mentors, he accepted the inevitable and actually became a very positive force in his successor’s transition.

Letting go, the CEO’s final reality, is a challenge each leader will unquestionably face when handing over governance to a successor.

Many CEOs go into the role believing that they will be different—that they will have little problem stepping down. However, when the horizon comes into view at the mid-point of their tenure, their attitudes suddenly shift—especially if their vision is not yet fully realized.

The status that comes with the position of CEO also brings power and, human nature being what it is, power is the most difficult force to surrender.

Such was the case with the CEO of a Fortune 500 company. An ambitious executive who very much wanted the top job, he finally achieved his goal and proved to be an effective, much-adored leader. However, when it came to discussing plans for stepping down, his ambivalence towards his successor surfaced strongly. Consequently, the board worried these mixed messages were getting in the way of making a final decision. Like many CEOs, his intellect understood the need to move on, but his emotional readiness lagged behind. With guidance from a variety of mentors, he accepted the inevitable and actually became a very positive force in his successor’s transition.

Letting go, the CEO’s final reality, is a challenge each leader will unquestionably face when handing over governance to a successor.

Strength from Knowledge

What are the remedies to the four realities of leadership experienced by every CEO? None apply to everyone equally. Still, bearing the following in mind may help guide you on your way:

- Be aware you are walking on the razors’ edge.

- Embrace the reality of life at the top.

- Draw strength from your knowledge.

- Stay confident. You were selected for a reason.

- Seek clarity and alignment with the board on strategic issues.

- Maintain your fortitude, alignment and composure.

- Seek multiple points of support from family, friends and mentors.

- Cultivate trusted advisors and accept their feedback.

- Pass the torch with grace, style and dignity.

Fuente: Chief Executive